Grey Skies, Grey Wagtails, Linnets, & a New Writing Companion … April 2024.

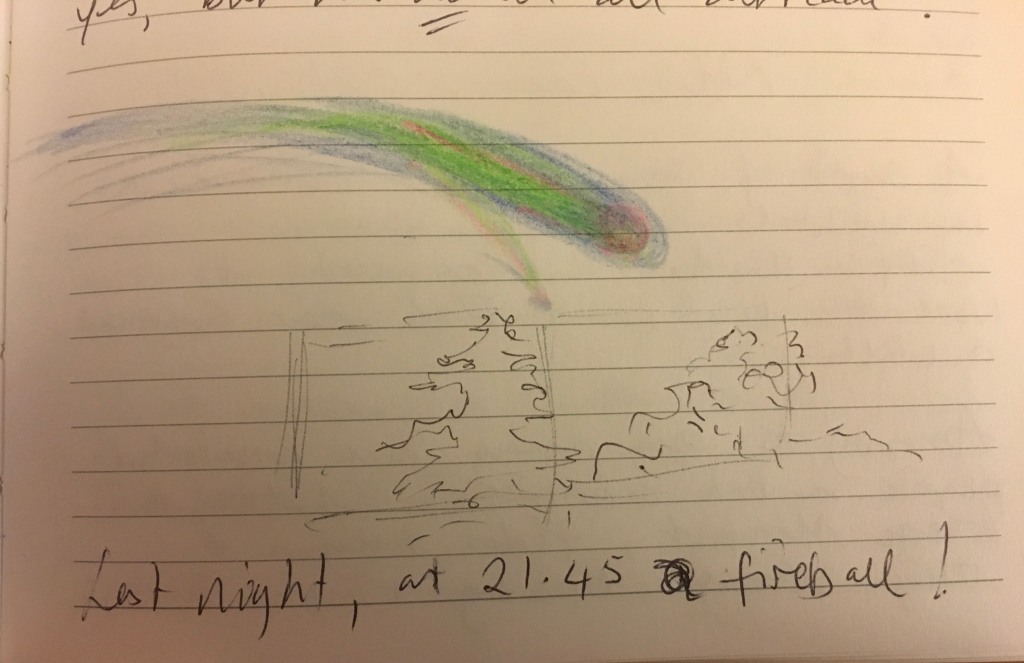

It’s been a chilly spring of grey-lidded skies and so very much rain. Sometimes, things feel far from ‘normal,’ and there is a kind of surreal, lucid edge around the lens of things, when I’m very aware the joint wildlife and climate crisis is playing out before our eyes. And of course, here in the UK, we are unfairly buffered from the worst effects unfolding. The rain caused a small landslip below the rookery on Hollow Lane in the village, bringing down a portion of the high bank. We make the weather now.

I’ve seen more grey or ‘water’ wagtails around this winter than I’ve seen before here; some have made pairs where there are semi-permanent ‘new streams,’ so I imagine they’ll breed. There are a pair in the farmyard opposite, making a buttercup splash of colour on the warm red roof tiles of the old threshing barn. There has been a boom in early flying insect life too, no doubt because of the damp, relatively warm conditions. There are big clouds of midges – large ones at that – that everyone is talking about in the village. Number plates from cars coming up on the road through the flooded water meadows, have been splatted like they haven’t been since the 1980s. The midges torment the horses in their boggy meadow, and they’ve had to wear fly masks that cover their eyes (and more specifically, their poor, tortured ears) as early in the year as I’ve known it. But that is easily sorted. And it does mean, as the first swallows arrive, that there will be more insect food available. A change from recent years.

Home Field, behind the house, is often a difficult one to farm. This year, a cover crop has gone in, that should recharge the soil a bit and benefit birds and insects with nectar then seed, and we were looking forward to some garden gate wildlife – but early on, subsequent storms have washed much of the seed and seedlings away. Often, a widening stream has run down the middle of it. But though it is looking patchy and bare, it still has enormous value for wildlife. Seemingly out of the blue, a substantial flock of linnets rose up from the field one day last month, and they’ve been here since. There have been small flocks about (less than a dozen) before and more among the gorse on the downs above us, but not as many as this on Home Field in decades. The nearest flocks had developed several fields away, on bird cover crops and field margins established over ten years and which have subsequently gone, replaced again by arable. I wonder if they are refugees from there? Either way, with a twinkling, twittering frisson of static, 80-100 of these sweetest of finches make bouncing passes over the house and my writing hut all day long.

They load the wires, then descend for the floodbourne weed seeds and cover crop below – persicaria (or redshank) mingles with dandelion, groundsel, charlock, knotgrass and chickweed. They often alight in my neighbour’s oak tree, and I can see them from my kitchen window: little streaky dun breasts, with rouge marks over their tiny lungs, and a lipstick kiss on their foreheads. I love them so much.

I can’t believe they’re here, but I worry about them. Their habitat is so ephemeral, so transient; like the temporary bloom in midges. It seems we’ve brought back numbers by creating a habitat for a few years, then taken it away again. I worry where they will nest; that the hedges here might not be enough. That the meagre, rain-damaged crop will further fail, be ploughed, begun again or turned back to arable. At my most devastated moments, when they come twittering over in flocks worthy of a nature reserve, I feel I am watching the fading fireworks of a dying star. Their voices and sound of hundreds of wings seem to come from far away in time. Those cardinal-rose coloured breasts and sweetly-streaked kissed polls are lifted straight from sentimental, Victorian colourised greeting cards. I almost can’t hold them in the here and now – already, they would be too painful, too easy to lose again. But the field could bloom, too. It could stay. And that lilting, bouncing flight, that bright twittering of numbers, is such a joy. I only wish we could sustain it.

The linnets are not my only new writing hut companion, overbrimming my heart. Meet Tansy Beetle. Soon-to-be companion of miles, and already, hearts and souls. I am, we are, utterly smitten. Though, just at the point when I’ve more writing to be done than ever, it might not have been my most timely decision. (Oh don’t be silly. Of course it is.)

Unexpected puppy in the writing hut area …

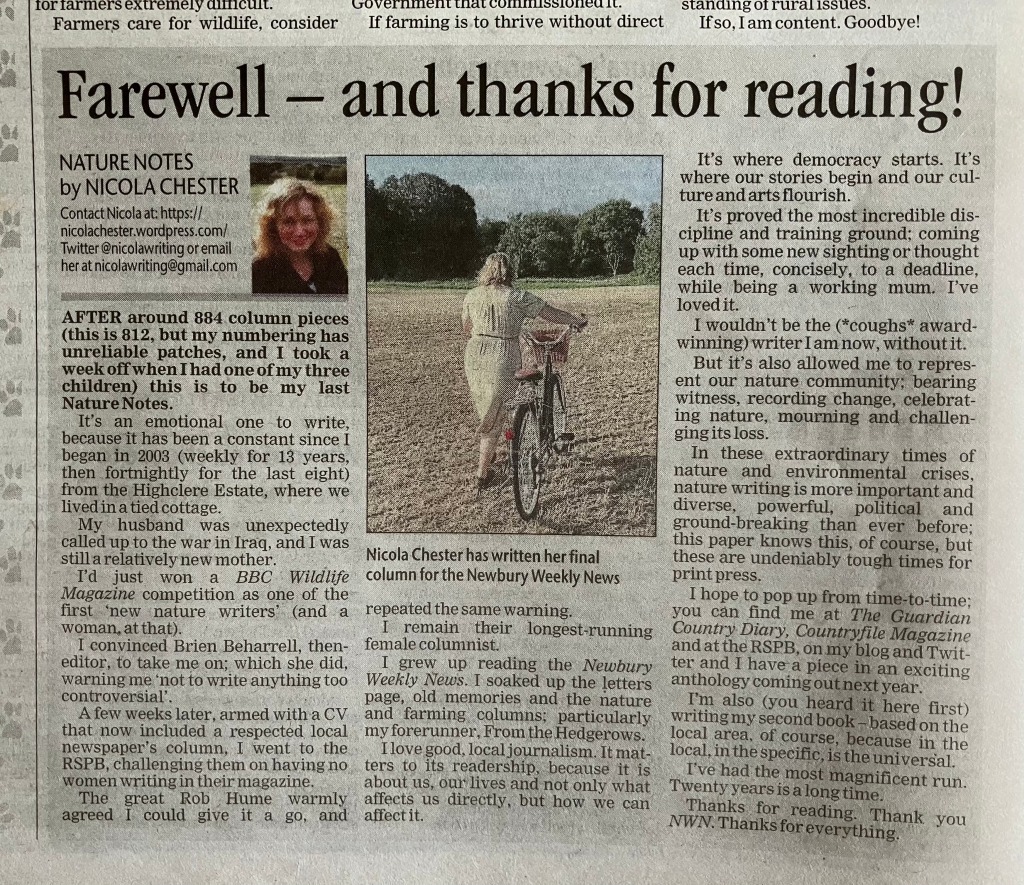

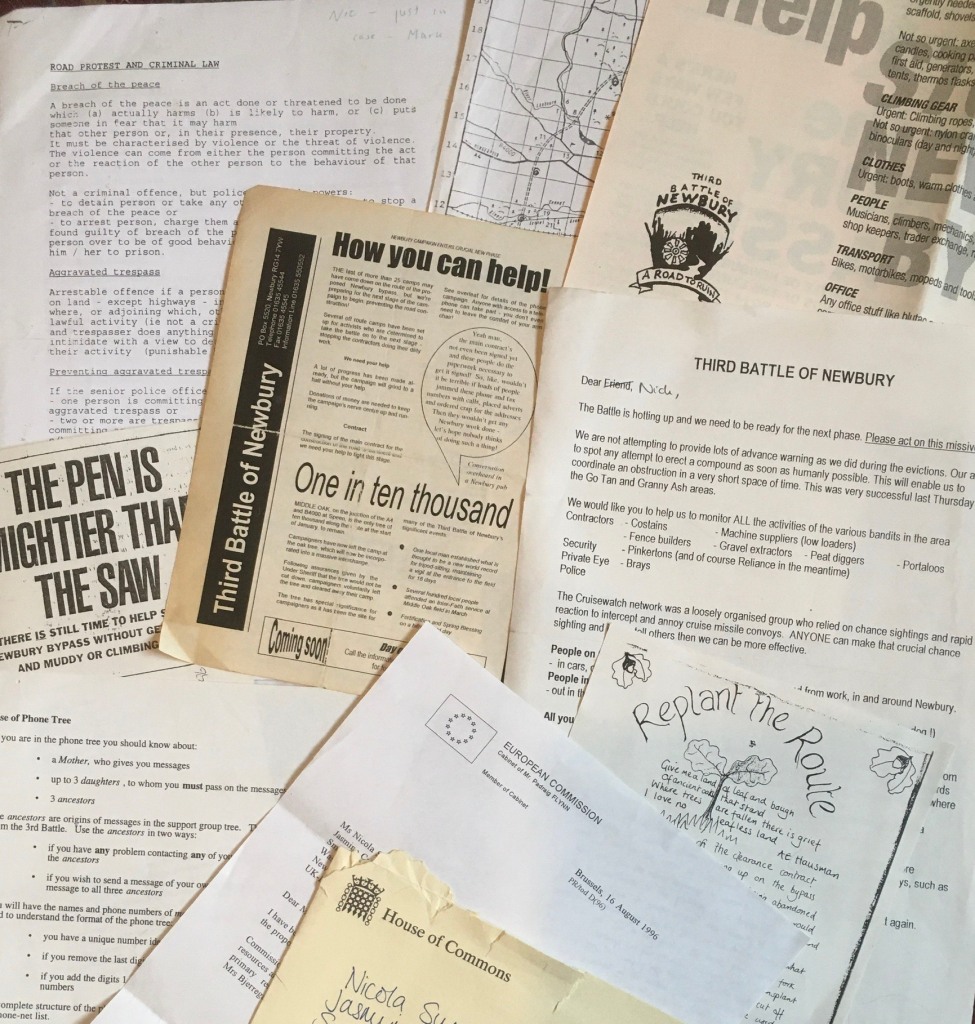

Articles and News …

My Guardian Country Diary this month is about early spring – and a cold, wet one at that, of course – on the downs. The contrasts of dapple-grey and white snag my eye as a deeply familiar marker of spring that I always forget to look for. So it comes almost as an unbidden memory each time. It’s there in the chalk tracks and cream-plough fields, hail-full clouds, a snow flurry against an iron sky, blossom by a flint wall. Spring on the downs has a look of the substrate that forms it – a blue-merle purling of flint and chalk. I walked up a few days later with the lovely Lucy Lapwing and was delighted to show her my little patch of the world. Particularly as she’d read my book, and was moved by it. I was honoured that Lucy interviewed me at the Gathering Festival at Wild Ken Hill in 2022. We were both a bit emotional to say the least, and it felt good to show her the ‘lapwing fields’ I’d written about. We heard a hopeful woodlark, listening on indrawn breaths, our hands involuntarily gone to our hearts. The piece is here: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2024/apr/03/country-diary-a-day-of-so-many-nature-interventions

My Countryfile Magazine Column for April is on the surprisingly radical and hopeful institution of Village Halls. Ours, like many around the country, is 100 years old this year. Whether it’s playgroups (mine or my children’s) parties, keep fit classes, farmer’s markets, ours or someone else’s wedding, fundraising quizzes and roof-raising barn dances, I can’t recall a time when a village hall event wasn’t on the calendar. I am very attached to them and, as long as diverse, healthy, rural communities survive, there will be a need for vibrant village halls, and uses for them that we haven’t even dreamt up yet. Writing this has sparked a future project. But that’s a ways off yet! The piece isn’t online yet, but you can find others here: https://www.countryfile.com/people/opinion/ Lynn Hatzius has surpassed herself with this wonderful illustration too.

I had the honour of joining Lady Carnarvon of Highclere Castle (of Downton Abbey fame) for her Friends of Highclere Castle Book Club. It was a homecoming of sorts, as we were working tenants on the estate almost 20yrs ago, and I’ve such fond memories of the place! It was still a time when estate staff were occasionally invited up to ‘The Big House’ (or ‘The Castle’) for drinks. Here we are in the Library – a favourite room. It has a ladder and of course, a secret door which doubles up as a bookshelf … and, if you’ve read my book, On Gallows Down, I took the old cottage door key back with me to show her – but lost my nerve and kept it safe in my pocket at the last minute.

And lastly and most excitingly, the 25th April sees the launch of a new book, Wild Service, that I have an essay in. Edited by Nick Hayes and Jon Moses, and featuring explosive and compelling writing from the likes of Nadia Shaikh, Guy Shrubsole, Amy-Jane Beer, Bryony Ella, Maria Fernandez-Garcia, Harry Jenkinson, Dal Kular, Sam Lee, Emma Linford, Paul Powesland and Romilly Swann, it’s a philosophy, a call to action, a meditation, a celebration and an invitation. And there’s a Book Club with each author, too! More here: https://twitter.com/i/status/1779797839100379480

“In Wild Service we meet Britain’s new nature defenders: an anarchic cast of guerilla guardians who neither own the places they protect, nor the permission to restore them. Still, they’re doing it anyway. This book is a celebration of their spirit and a call for you to join. So, whether you live in the countryside or the city, want to protect your local river or save our native flora, this is your invitation to rediscover the power in participation – the sacred in your service.“

Thanks so much for reading – a lot to pack in this month. And excuse me, I think puppy wants to go out …